Ensemble interpretation

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

|

| Introduction Glossary · History |

|

Background

|

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Formulations

|

|

Equations

|

|

Interpretations

|

|

Advanced topics

|

|

Scientists

Bell · Bohm · Bohr · Born · Bose

de Broglie · Dirac · Ehrenfest Everett · Feynman · Heisenberg Jordan · Kramers · von Neumann Pauli · Planck · Schrödinger Sommerfeld · Wien · Wigner |

The ensemble interpretation, or statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics, is an interpretation that can be viewed as a minimalist interpretation; it is a quantum mechanical interpretation that claims to make the fewest assumptions associated with the standard mathematical formalization. At its heart, it takes to the fullest extent the statistical interpretation of Max Born for which he won Nobel Prize in Physics.[1] The interpretation states that the wave function does not apply to an individual system – or for example, a single particle – but is an abstract mathematical, statistical quantity that only applies to an ensemble of similarly prepared systems or particles. Probably the most notable supporter of such an interpretation was Albert Einstein:

The attempt to conceive the quantum-theoretical description as the complete description of the individual systems leads to unnatural theoretical interpretations, which become immediately unnecessary if one accepts the interpretation that the description refers to ensembles of systems and not to individual systems.

—Albert Einstein[2]

To date, probably the most prominent advocate of the ensemble interpretation is Leslie E. Ballentine, Professor at Simon Fraser University, and writer of the graduate-level textbook "Quantum Mechanics, A Modern Development".[3]

The ensemble interpretation, unlike many other interpretations of quantum mechanics, does not attempt to justify, or otherwise derive, or explain quantum mechanics from any deterministic process, or make any other statement about the real nature of quantum phenomena; it is simply a statement as to the manner of wave function interpretation.

Contents |

Measurement and collapse

The attraction of the ensemble interpretation is that it immediately dispenses with the metaphysical issues associated with reduction of the state vector, Schrödinger cat states, and other issues related to the concepts of multiple simultaneous states. As the ensemble interpretation postulates that the wave function only applies to an ensemble of systems, there is no requirement for any single system to exist in more than one state at a time, hence, the wave function is never physically required to be "reduced". This can be illustrated by an example:

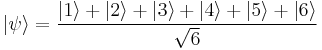

Consider a classical die. If this is expressed in Dirac notation, the "state" of the die can be represented by a "wave" function describing the probability of an outcome given by:

It is clear that on each throw, only one of the states will be observed, but it is also clear that there is no requirement for any notion of collapse of the wave function/reduction of the state vector, or for the die to physically exist in the summed state. In the ensemble interpretation, wave function collapse would make as much sense as saying that the number of children a couple produced, collapsed to 3 from its average value of 2.4.

The state function is not taken to be physically real, or be a literal summation of states. The wave function, is taken to be an abstract statistical function, only applicable to the statistics of repeated preparation procedures, similar to classical statistical mechanics. It does not directly apply to a single experiment, only the statistical results of many.

Criticism

David Mermin sees the Ensemble interpretation as being motivated by an adherence ("not always acknowledged") to classical principles.

"For the notion that probabilistic theories must be about ensembles implicitly assumes that probability is about ignorance. (The 'hidden variables' are whatever it is that we are ignorant of.) But in a non-deterministic world probability has nothing to do with incomplete knowledge, and ought not to require an ensemble of systems for its interpretation".

He also emphasises the importance of describing single systems, rather than ensembles.

"The second motivation for an ensemble interpretation is the intuition that because quantum mechanics is inherently probabilistic, it only needs to make sense as a theory of ensembles. Whether or not probabilities can be given a sensible meaning for individual systems, this motivation is not compelling. For a theory ought to be able to describe as well as predict the behavior of the world. The fact that physics cannot make deterministic predictions about individual systems does not excuse us from pursuing the goal of being able to describe them as they currently are."[4]

Single particles

According to proponents of this interpretation, no single system is ever required to be postulated to exist in a physical mixed state so the state vector does not need to collapse.

It can also be argued that this notion is consistent with the standard interpretation in that, in the Copenhagen interpretation, statements about the exact system state prior to measurement can not be made. That is, if it were possible to absolutely, physically measure say, a particle in two positions at once, then quantum mechanics would be falsified as quantum mechanics explicitly postulates that the result of any measurement must be a single eigenvalue of a single eigenstate.

Criticism

Arnold Neumaier finds limitations with the applicability of the ensemble interpretation to small systems.

"Among the traditional interpretations, the statistical interpretation discussed by Ballentine in Rev. Mod. Phys. 42, 358-381 (1970) is the least demanding (assumes less than the Copenhagen interpretation and the Many Worlds interpretation) and the most consistent one. It explains almost everything, and only has the disadvantage that it explicitly excludes the applicability of QM to single systems or very small ensembles (such as the few solar neutrinos or top quarks actually detected so far), and does not bridge the gulf between the classical domain (for the description of detectors) and the quantum domain (for the description of the microscopic system)". (spelling amended) [5]

Schrödinger's cat

The ensemble interpretation states that superpositions are nothing but subensembles of a larger statistical ensemble. That being the case, the state vector would not apply to individual cat experiments, but only to the statistics of many similar prepared cat experiments. Proponents of this interpretation state that this makes the Schrödinger's cat paradox a trivial non-issue. However, the application of state vectors to individual systems, rather than ensembles, has explanatory benefits, in areas like single-particle twin-slit experiments and quantum computing (see Schrödinger's cat applications). As an avowedly minimalist approach, the ensemble interpretation does not offer any specific alternative explanation for these phenomena.

The frequentist probability variation

The claim that the wave functional approach fails to apply to single particle experiments cannot be taken as a claim that quantum mechanics fails in describing single-particle phenomena. In fact, it gives correct results within the limits of a probabilistic or stochastic theory.

Probability always require a set of multiple data, and thus single-particle experiments are really part of an ensemble — an ensemble of individual experiments that are performed one after the other over time. In particular, the interference fringes seen in the double-slit experiment require repeated trials to be observed.

The quantum Zeno effect

Leslie Ballantine promoted the ensemble interpretation in his book Quantum Mechanics, A Modern Development. In it,[6] he described what he called the "Watched Pot Experiment". His argument was that, under certain circumstances, a repeatedly measured system, such as an unstable nucleus, would be prevented from decaying by the act of measurement itself. He initially presented this as a kind of reductio ad absurdum of wave function collapse.[7]

The effect has been shown to be real. (It is more widely known as the quantum Zeno effect). Ballentine later wrote papers claiming that it could be explained without wave function collapse.[8]

Earlier Classical Ensemble Ideas

Early proponents of statistical approaches regarded quantum mechanics as an approximation to a classical theory. John Gribbin writes:

"The basic idea is that each quantum entity (such as an electron or a photon) has precise quantum properties (such as position or momentum) and the quantum wavefunction is related to the probability of getting a particular experimental result when one member (or many members) of the ensemble is selected by an experiment"

However, hopes for turning quantum mechanics back into a classical theory were dashed. Gribbin continues:

"There are many difficulties with the idea, but the killer blow was struck when individual quantum entities such as photons were observed behaving in experiments in line with the quantum wave function description. The Ensemble interpretation is now only of historical interest."[9]

Willem de Muynck describes an "objective-realist" version of the ensemble interpretation featuring counterfactual definiteness and the "possessed values principle", in which values of the quantum mechanical observables may be attributed to the object as objective properties the object possesses independent of observation. He states that there are "strong indications, if not proofs" that neither is a possible assumption.[10]

See also

References

- ^ "The statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics". Nobel Lecture. December 11, 1954. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1954/born-lecture.pdf.

- ^ Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, ed. P.A. Schilpp (Harper & Row, New York)

- ^ Leslie E. Ballentine (1998). Quantum Mechanics: A Modern Development. World Scientific. Chapter 9. ISBN 9810241054. http://books.google.com/books?id=sHJRFHz1rYsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:Quantum+intitle:Mechanics+intitle:A+intitle:Modern+intitle:Development&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA230,M1.

- ^ Mermin, N.D. The Ithaca interpretation

- ^ Arnold Neumaier's FAQ

- ^ Leslie E. Ballentine. Quantum Mechanics: A Modern Development. p. 342. ISBN 9810241054. http://books.google.com/books?id=sHJRFHz1rYsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:Quantum+intitle:Mechanics+intitle:A+intitle:Modern+intitle:Development&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA342,M1.

- ^ "Like the old saying "A watched pot never boils", we have been led to the conclusion that a continuously observed system never changes its state! This conclusion is, of course false. The fallacy clearly results from the assertion that if an observation indicates no decay, then the state vector must be |y_u>. Each successive observation in the sequence would then "reduce" the state back to its initial value |y_u>, and in the limit of continuous observation there could be no change at all. Here we see that it is disproven by the simple empirical fact that [..] continuous observation does not prevent motion. It is sometimes claimed that the rival interpretations of quantum mechanics differ only in philosophy, and can not be experimentally distinguished. That claim is not always true. as this example proves" ".Ballentine, L. Quantum Mechanics, A Modern Development(p 342)

- ^ "The quantum Zeno effect is not a general characteristic of continuous measurements. In a recently reported experiment [Itano et al., Phys. Rev. A 41, 2295 (1990)], the inhibition of atomic excitation and deexcitation is not due to any ‘‘collapse of the wave function,’’ but instead is caused by a very strong perturbation due to the optical pulses and the coupling to the radiation field. The experiment should not be cited as providing empirical evidence in favor of the notion of ‘‘wave-function collapse.’’" Physical Review

- ^ John Gribbin, Q is for Quantum

- ^ Quantum Mechanics the Way I see it

External links

- Quantum mechanics as Wim Muynk sees it

- Einstein's reply to criticisms

- Kevin Aylwards's account of the ensemble interpretation

- Detailed ensemble interpretation by Marcel Nooijen

- Pechenkin, A.A. The early statistical interpretations of quantum mechanics

- Krüger, T. An attempt to close the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen debate

- Duda, J. Four-dimensional understanding of quantum mechanics